|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Besides light, water and carbon dioxide, plants need nutrients to grow, produce biomass and feed animals and microbes. Nutrients fall into two categories: |

||||||||||||

|

|

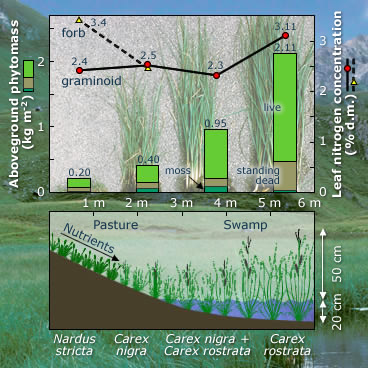

Plants do not commonly derive their nutrients directly from the atmosphere or parent rock, but from pools stored in the soil where all nutrients can periodically fall short. It is not the total amount of nutrient elements in the soil which determines plant growth, but their availability. Nutrients become available in large part due to biological processes in the soil. The largest nutrient fraction is commonly locked up in recalcitrant (slowly decomposing) soil humus. It is not the concentration in the soil solution which is ecologically relevant, but the nutrient release rate, which is often closely tied to uptake by plants. Hence, the soil nutrient status of natural ecosystems cannot be studied by conventional chemical analysis of soil extracts, but needs to be assessed via soil microbial activity (e.g. the rate of mineralisation). Because the origin of nitrogen is the atmosphere, and because natural nitrogen availability to plants is under biological control, N nutrition is commonly treated separately from mineral nutrition. Steep nutrient gradients lead to dramatic differences in plant biomass and species composition even at very high altitudes (Fig. 2, 300 m above the treeline in the Alps, Wattens/Tyrol, 2300 m). A gully with no outlet traps leached nutrients from surrounding slopes. Rainfall in this area is high (> 1200 mm/year with a peak during the growing season), hence upslope plants never experience any moisture shortage. Note that leaf nutrient concentrations vary little across this 10-fold gradient of plant vigour, and high leaf nitrogen concentrations occur at both ends of the transect. What differs is the amount of biomass, and thus nitrogen in biomass, per unit land area. Remember:

|

2 - Moisture gradients are nutrient gradients. |

29 August 2011 |

||

| |

||